Biolubricants and Industry Standards: Navigating the Compliance Landscape with Less ‘Friction’

Dr Konstantinos Drousiotis

Senior Research Analyst

A lubricant is a substance designed to reduce friction and wear between surfaces in relative motion. Its properties allow it to perform various functions, such as dissipating heat, removing wear debris, delivering additives to the contact area, conduct power, and to protect or seal surfaces. By minimizing wear and tear, lubricants help extend the operational lifespan of mechanical systems 1 1 Alang, M.B. et al. (2018) ‘Synthesis and characterisation of a biolubricant from Cameroon palm kernel seed oil using a locally produced base catalyst from plantain peelings’, Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 08(03), pp. 275–287. doi:10.4236/gsc.2018.83018. .

Fats and oils have been used as lubricants throughout history; however, the systematic commercialization of modern biolubricants did not occur until the late twentieth century. This development was driven by environmental concerns, with policies driving research and development efforts and creating market demand. By the 2020s, biolubricants were estimated to constitute approximately 2% of the global lubricants market.

Currently, there are many distinct methods for defining a “biolubricant” some of which are listed in the overview that follows. When initially introduced, biolubricant broadly referred to any lubricant that contained a sizable quantity of biodegradable ingredients thus rendering the final product susceptible to microbial decomposition when disposed of. The terms “biodegradable lubricant” and “bio-lubricant,” are often used interchangeably in literature.

In general, lubricants are made from a mix of ingredients, comprising of a base oil plus a mixture of additives. The typical ratio of base oil and additives in the lubricant is 90:10 22 Ahmad, U. et al. (2022) ‘A review on properties, challenges and commercial aspects of eco-friendly biolubricants productions’, Chemosphere, 309, p. 136622. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136622. .

Base oils for conventional fossil-based lubricants include synthetic liquids (e.g., polyolefins, esters, fluorocarbons etc.), refined oil and mineral oils. Vegetable oils are predominantly used in the production of biolubricants3 3 Narayana Sarma, R. and Vinu, R. (2022) ‘Current status and future prospects of biolubricants: Properties and applications’, Lubricants, 10(4), p. 70. doi:10.3390/lubricants10040070. . Biolubricant can also be produced from animal fats, plant polymeric carbohydrates, and wax esters4. Vegetable oils represent around 81% of the base oils used to produce biolubricants, with the remainder being animal fats. A wide range of vegetable oils are used as base stocks including edible (e.g., sunflower oil, rapeseed oil and soybean oil) and non-edible (e.g., jatropha oil, neem and karanja) oils 44 Kurre, S.K. and Yadav, J. (2023) ‘A review on bio-based feedstock, synthesis, and chemical modification to enhance tribological properties of biolubricants’, Industrial Crops and Products, 193, p. 116122. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.116122. , 5 5 Caleb Abiodun Popoola and Titus Yusuf Jibatswen (2024) ‘Non-edible vegetable oils as bio-lubricant basestocks: A Review’, Open Access Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, 6(2), pp. 080–086. doi:10.53022/oarjet.2024.6.2.0040. . Common animal fats used as base oils include beef tallow, pork lard and fish oil such as cod liver oil.

Technical limitations restrict the use of pure vegetable oils as lubricants and chemical modifications are used to enhance their lubricity and improve oxidative stability. One such method is the transesterification of triglycerides to produce fatty acid alkyl esters. This process reduces the coefficient of friction while maintaining the naturally high viscosity indexes of vegetable oils relative to mineral oils.

The lubricating properties of trans-esterified vegetable oils are influenced by the molar ratio of triglyceride to alcohol, type of alcohol, catalyst type, feedstock fatty acid content, its unsaturation levels and chain length 6 6 Uppar, R., Dinesha, P. and Kumar, S. (2022) ‘A critical review on vegetable oil-based bio-lubricants: Preparation, characterization, and challenges’, Environment, Development and Sustainability, 25(9), pp. 9011–9046. doi:10.1007/s10668-022-02669-w. . Due to these chemical modifications, the resulting product is sometimes referred to as a “synthetic lubricant.” However, this terminology may lead to the misconception that these lubricants originate from mineral oils rather than renewable sources.

The second essential component of lubricants are additives which serve to improve the performance of base oils , additives can act in three different ways: a) either improve some of the properties of the base oil or b) reduce some of the characteristics of the base oil or c) ultimately introduce new features to the base oil. They include maintainers (e.g. dispersants and antioxidants), triboimprovers (e.g. anti-wear and friction modifiers) and rheo-improvers (e.g. viscosity index improvers and pour point depressants) 7 7 Barbera, E. et al. (2022) ‘Recent developments in synthesizing biolubricants — a review’, Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 14(3), pp. 2867–2887. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-02438-9. .

End-use industries and applications of biolubricants

Figure 1. Breakdown of end-use applications in the biolubricants market, showcasing key industry sectors and their market shares.

The biolubricants industry, with a worldwide demand under 350 kt, constitutes slightly over 2% of the finished lubricant global market and is highly segmented 8 8 Kurre, S.K. and Yadav, J. (2023) ‘A review on bio-based feedstock, synthesis, and chemical modification to enhance tribological properties of biolubricants’, Industrial Crops and Products, 193, p. 116122. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.116122..

The automotive and other transportation segments held the lion’s share of the market in terms of volume 9Biolubricants market size, share, Growth Report, 2032 (no date) Biolubricants Market Size, Share, Growth Report, 2032..

Manufacturing, mining & construction and agriculture occupy the first, second and third largest shares in end-use industries. The largest market share belongs to the hydraulic fluids category 10 10 Joshi, J.R., Bhanderi, K.K. and Patel, J.V. (2023) ‘Waste cooking oil as a promising source for Bio Lubricants- A Review’, Journal of the Indian Chemical Society, 100(1), p. 100820. doi:10.1016/j.jics.2022.100820., 11 11 Bio-lubricants market (no date) The Brainy Insights. Available at: https://www.thebrainyinsights.com/report/bio-lubricants-market-14041?srsltid=AfmBOooMaQoMTmFAbJjymy…, 12 12 Institute for Fluid Power Drives and Systems (no date) H1, PUB – Bio-Based Hydraulic Fluids in Mobile Machines – Substitution Potential in Construction Pro… – RWTH AACHEN UNIVERSITY IFAS – English. Available at: https://www.ifas.rwth-aachen.de/cms/ifas/das-institut/aktuelle-meldungen/~emqlh/pub-biobasierte-hyd…, 13 13 ltd, R. and M. (no date) Biolubricants market size, competitors, Trends & Forecast, Biolubricants Market Size, Competitors, Trends & Forecast. Available at: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/biolubricant?srsltid.

Bio-based lubricants are frequently utilized as hydraulic fluids to enhance operations such as harvesters, cranes, tractors, or load carriers in forests. Other prominent applications with uses in various industries include automotive engine oils, grease, chainsaw oils and mold release agents.

Regional standards within Europe include the EU Ecolabel with identifiable certified products applicable in all industries mentioned in Figure 1 14 14 Products and provider (EU Ecolabel). Available at: https://eu-ecolabel.de/en/for-companies/products-and-provider?tx_euecolabelproducts_product%5Bactio…. The label requires three essential sustainability attributes (biodegradability, accumulation and toxicity) and states that an emulsion should satisfy the following 15 15 European Commission: Directorate-General for Environment, The EU Ecolabel for lubricants, Publications Office of the European Union, 2023, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2779/647506:

- ‘Final products should not contain substances that are both non-biodegradable and potentially bio-accumulative’

- ‘Meets stringent limits on the aquatic toxicity of substances and ingredients’

Additionally, since January 2019, the EU Ecolabel has included an extra criterium that bio-lubricants must have a ‘minimum bio-based content of 25%’ in case the awarded manufacturer intends to brand it as a ‘biolubricant’ 16 16 EU standards for bio-based surfactants, solvents, lubricants (2024a) Beta Analytic – ASTM D6866 Lab. Available at: https://www.betalabservices.com/biobased/cen-bio-based-standards.html . The bio-based carbon content can be measured according to ASTM D6866, CEN/TS 16137 (SPEC 91236), EN 16640 or EN 16785-1 .

To exemplify the first two requirements, the European Commission has created product categories based on the likelihood of the lubricants escaping to the environment depending on their end-use application. The category descriptors which refer to different levels of leakage are PLL (i.e., ‘partial loss lubricant’) which includes open gear oils, stern tube oils, two-stroke oils and oils for temporary corrosion protection whereas ALL (i.e., ‘accidental loss lubricant’) includes hydraulic fluids, metalworking fluids and gear oils for closed gear. In the case of chainsaw oils, wire rope lubricants and concrete release agents the full volume of lubricant is likely to disperse and therefore these belong in the final category known as ‘total loss lubricants’ i.e., TLL.

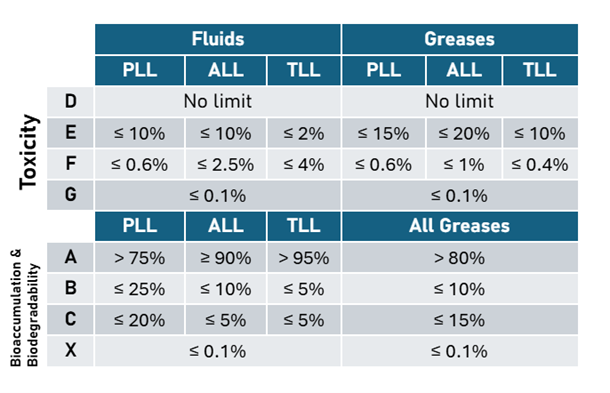

The commission has created the Lubricant Substance Classification list (i.e., LuSC) with the intention to assign ratings to said categories based on the fluids’ or greases’ biodegradability, bioaccumulation and aquatic toxicity levels to assist manufacturers with choosing approved components and additives (Table 1).

Table 1. Minimum required weight percentage of biodegradable material and the maximum allowed weight percentage of aquatic toxic substances by product category of lubricants, as instructed by EU Ecolabel.

Key:

- A – Readily biodegradable; not bio accumulative

- B – Inherently biodegradable; not bio accumulative

- C – Not biodegradable; not bio accumulative

- X – Not biodegradable; bio accumulative

- D – Non-Toxic

- E – Harmful

- F – Toxic

- G – Very Toxic

Country-specific standards include US BioPreferred Program which, as the name suggests focusses, mainly on the renewability aspect of bio lubricants having established a minimum of 72% bio-based content for multipurpose grease, 44% for hydraulic oil, 34% for two-cycle engine oil 17 17 DOD Sustainable Products Center (no date) DENIX. Available at: https://www.denix.osd.mil/spc/demonstrations/completed/btwceo/.

Another national standard which covers multiple industries 18 18 Blue Angel, lubricant, hydraulic fluid, biological degradable, low emissions (no date) Blue Angel. Available at: https://www.blauer-engel.de/en/productworld/lubricants-and-hydraulic-fluids/lubricants?mfilter%5B0%… is the German ecolabel ‘Blue Angel’. This was the first national labelling scheme for lubricants developed back in 1988 19 19 Cheng, N. et al. (2008) Ascertaining the Biodegradability and Aquatic Toxicity of Biolubri Greasekote 100 Environmental Acceptable Lubricant (EAL) in Accordance with OECD 301F and OECD 201 Test Methods . The latter requires that 95% of the product mass must be readily biodegradable, achieving more than 70% biodegradation, as defined in the standard, within 28 days of disposal. Further, the certification requires that the substance should not bioaccumulate and not lead to chronic aquatic toxicity similarly to EU Ecolabel. The scheme does not require renewable content, but if renewable raw materials are used, they must comply with the requirements of a certification system covering sustainable production (e.g., RSB, ISCC etc).

Industry-Specific and product-type lubricant standards: tailoring performance to application needs

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates incidental discharges from commercial vessels operating in U.S. waters through a permit system known as the Vessel General Permit (VGP). The VGP mandates the use of Environmentally Acceptable Lubricants (EALs) in all oil-to-water interfaces on merchant vessels of 79 feet or longer, sailing within three nautical miles of US coast and inland waters 20 20 Vessel general permit: Exxonmobil Marine (no date) Vessel General Permit | ExxonMobil marine. Available at: https://www.exxonmobil.com/en/marine/technicalresource/marine-resources/vessel-general-permit-guidelines . The EALs definition gives emphasis to ‘biodegradability’, ‘non-toxicity’ and ‘bio-accumulation’ in the same way EU Ecolabel definition does, however, it omits any renewable content requirements 21 21 Tilley Distribution (2024) The viability of environmentally acceptable lubricants, Tilley Distribution. Available at: https://www.tilleydistribution.com/insights/green-lube-the-market-viability-of-environmentally-acce…. VGP orders that EALs should not bio-accumulate in such a way that aquatic or terrestrial organisms absorb these chemical substances faster than they can be lost or eliminated by catabolism and excretion. In terms of biodegradability, VGP adds that EALs should ‘readily’ biodegrade (i.e. more than 60% of the test material carbon must be converted to carbon dioxide within 28 days) 22 22 Advanced Solutions International, Inc. (December 2020) Feature. Available at: https://www.stle.org/files/TLTArchives/2020/12_December/Feature.aspxcomplying with either OECD Test Guidelines 302C (>70% biodegradation after 28 days) or OECD Test Guidelines 301 A-F (>20% but <60% biodegradation after 28 days).

It is noteworthy to mention that most petroleum-based lubricants degrade approximately 15-25% during that period, therefore inadvertently favouring the use of EALs derived from vegetable oils, especially over mineral oils 23 23 Tilley Distribution (2024a) The viability of environmentally acceptable lubricants, Tilley Distribution. Available at: https://www.tilleydistribution.com/insights/green-lube-the-market-viability-of-environmentally-acceptable-lubricants/ . However, due to the degradation value set at 60% of the content within 28 days, it means that, in practice, lubricating oil considered to be biodegradable can contain up to 50% of mineral oil base.

Another national labelling scheme, the Swedish Standard SS155434: 2015 applies to hydraulic oils only and places limits for toxicity as well as ordering for biodegradability however it does not set any bioaccumulation limits 24Technical Committee of Petroleum Additive Manufacturers in Europe (2018) DIFFERENT APPROACHES TO BIOLUBRICANTS – Clarification Paper. tech.. The equivalent standard for lubricant greases is SS155470 which orders that that the base fluid in the lubricating grease should be biodegradable as tested through a relevant standard e.g. ISO14593, with minimal aquatic toxicity. Similarly to SS155434, it sets no bioaccumulation limits.

The OSPAR (OSlo and PARis) Convention is an international agreement aimed at protecting the marine environment of the North-East Atlantic sea. The agreement was introduced in 1998 and was signed by 15 governments and the EU 25 25 Wennberg , A.C., Petersen , K. and Grung, M. (2017) Vol M-911|2017, Biodegradation of selected offshore chemicals: Evaluering av nedbrytningsegenskaper for utvalgte offshorekjemikalier. rep., pp. 1–118. . The OSPAR Hazardous Substances Strategy aims to prevent maritime pollution by continuously reducing discharges, emissions and losses of hazardous substances. The convention determines the level of impact of chemicals and hazardous substances in the marine environment through the measurement of marine toxicity, biodegradation and bioaccumulation.

The agreement requires that organic substances need to meet at least two of the following pre-screening testing requirements: i) Biodegradability ≥60% in 28 days according to the OECD 306 test method., ii) Bioaccumulation potential log Pow ≤ 3 or molecular weight ≥ 700 and iii) Acute toxicity LC50 or EC50 ≥10mg/l, to be included in OSPAR compliant lubricant formulations 26 26 (2020) OSPAR compliant synthetic base fluids | Cargill.

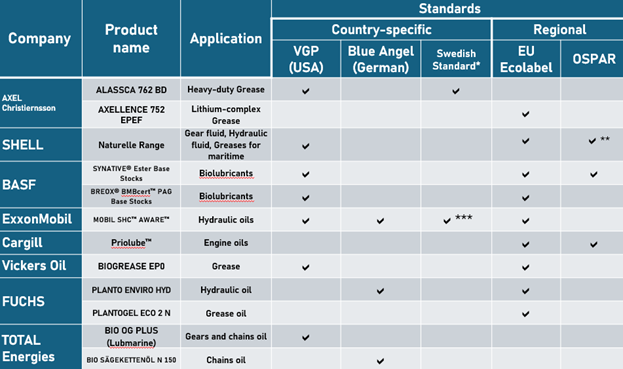

Table 2. Certified lubricants and greases from various companies

*SS includes both greases (SS155470) and hydraulic oils (SS15543)

**S4 Grease U68AP 1.5 only

*** Hydraulic oil 68 only

It becomes evident that these international bodies have as a common denominator that a biolubricant must be biodegradable, non-toxic and will not bioaccumulate. However, lubricants labelled under Blue Angel, European Ecolabel and Swedish Standard SS 155434 are generally regarded as VGP-compliant 27 27 Biodegradable hydraulic fluids standards, around the world (no date) Lubrizol360.com. Available at: https://360.lubrizol.com/2020/Biodegradable-Hydraulic-Fluids-Standards-Around-the-World, 28 28 Environmentally acceptable lubricants (eals) (no date a) IQLubricants. Available at: https://iqlubricants.iql-nog.com/content/44-environmentally-acceptable-lubricants-eals rendering it easier for a producer to market their product in both continents for the marine industry. Table 2 provides examples of biolubricants and their compliance with various lubricant standards.

In conclusion, the biolubricants industry has made significant strides in aligning with global sustainability goals, driven by stringent environmental standards and certifications. From the EU Ecolabel and Blue Angel to the U.S. Vessel General Permit (VGP) and OSPAR, these standards emphasize biodegradability, non-toxicity, and non-bioaccumulation as key criteria for environmentally acceptable lubricants. While regional and industry-specific standards vary in their requirements – such as renewable content or biodegradation thresholds – they collectively push manufacturers toward greener formulations.